Indonesia's EV Ecosystem in 2025: Progress and Regional Leadership Prospects

Highlights

- Indonesia's EV sales hit record highs in 2024, with 43,188 battery electric vehicles (BEVs) sold, a 151% increase from the previous year, yet penetration remains low at just 5% of total car sales.

- Two-wheelers remain key to scale, with Indonesia projected to become the world's third-largest electric two-wheeler market by 2030, reaching ~2 million units annually.

- Public charging infrastructure lags adoption: With only ~1,500 public charging stations nationwide by 2024, Indonesia targets over 63,000 by 2030. PLN and VinFast each plan tens of thousands more to support national electrification.

- Indonesia's nickel-driven EV battery advantage is at risk, as global automakers increasingly shift to LFP (lithium iron phosphate) batteries, which don't require nickel, due to cost, safety, and supply stability.

- Despite limited lithium resources, Indonesia seeks to stay relevant in LFP manufacturing by attracting cell plant investments and expanding battery material recycling and processing capabilities.

- Chinese brands like BYD, Wuling, and Chery dominate the BEV segment, aided by local assembly, VAT incentives, and low-cost models. Domestic players like GESITS continue to struggle with scale and price competitiveness.

- Thailand and Vietnam still outpace Indonesia in EV ecosystem maturity, with Thailand selling over 70,000 EVs in 2024 (12.25% of market share) and Vietnam reaching 16% share - driven by faster charging rollout and stronger export readiness.

- Policy direction remains central, with analysts urging more coherent sub-national regulations, transparent incentive allocation, and faster localization support to unlock long-term competitiveness.

GDP Contribution

| 2024 | 2030 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Pessimistic | Moderate | Optimistic | |

| US$ Billion* | 13.4 | 29.7 | 42.7 | 80.6 |

| % of GDP | ~0.9 | ~1.5 | ~2.2 | ~4.2 |

| CAGR | -- | 13.6% | 21.5% | 35.1% |

Employment Contribution

| 2024 | 2030 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Pessimistic | Moderate | Optimistic | |

| Thousand* | 100 | 199 | 287 | 541 |

| % of workforce | ~0.9 | ~0.14 | ~0.20 | ~0.38 |

| CAGR | -- | 12.3% | 18.7% | 32.4% |

BEV Sales Growth

151%

Year-on-year increase in 2024

EV Market Penetration

5%

Of total car sales in 2024

Charging Stations

1,566

Public stations nationwide (2024)

Introduction

Relatively shielded from the direct impact of recent trade and tariff debacles, Indonesia's ambition to become Southeast Asia's EV industry hub warrants renewed attention. While many of its traditional export sectors face uncertainty under the new 32% U.S. tariffs, Indonesia's EV ecosystem, rooted in domestic sales of 43,188 BEV cars and over 100,000 electric motorcycles in 2024, is driven by local demand and regional battery exports rather than U.S. markets.

From minerals to markets, Indonesia is intensifying efforts to build a competitive EV and battery supply chain, leveraging its world-leading nickel reserves and attracting large-scale investments in both battery manufacturing and vehicle production. Government incentives, including VAT exemptions, production subsidies, and local content mandates, have sparked strong investor interest and rising EV sales, especially in two-wheelers. However, persistent challenges remain: limited charging infrastructure, technology shifts in global battery chemistry, and uneven sub-national policy implementation all risk slowing progress.

The government targets 2 million electric cars and 12.9 million electric two-wheelers by 2030, supported by industrial plans to expand battery cell capacity to over 140 GWh and produce nearly 1 million tons of battery-grade nickel annually. In 2024, electric two-wheeler sales surpassed 100,000 units for the first time, while BEV car sales reached 43,188 units, marking a 151% year-on-year growth.

Yet, Indonesia's strategy, historically reliant on nickel-based batteries, is now being tested by the rise of LFP batteries, which do not require nickel and are rapidly gaining favor in China and India. At the same time, regional rivals like Thailand and Vietnam are advancing faster in ecosystem readiness, export orientation, and infrastructure rollout.

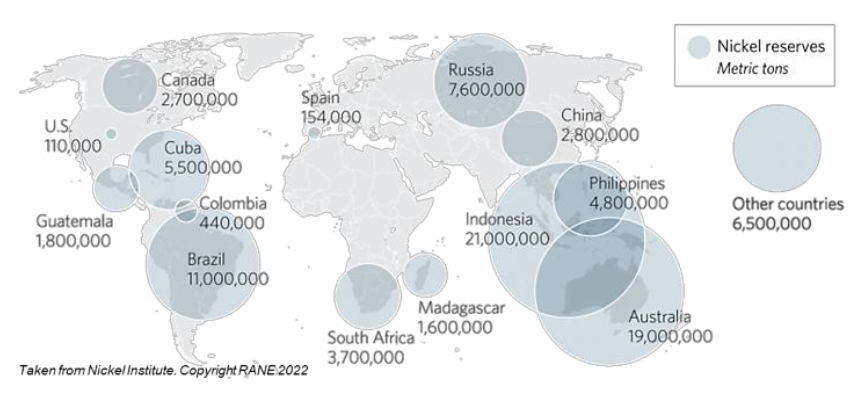

1. Nickel Dominance, Battery Supply Chain, and EV Manufacturing

Nickel Mining

Indonesia holds the world's largest nickel reserves, estimated at over 55 million metric tons (or 21 million metric tons using narrower base). These reserves are central to the country's EV strategy, particularly through production of mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP), an intermediate product used in nickel-rich battery chemistries (e.g., NMC). High-pressure acid leach (HPAL) facilities are already operational in major industrial zones like Morowali and Weda Bay, supplying battery materials domestically and abroad.

In 2023, Indonesia produced 2.2 million metric tons of nickel, up from 358,000 tons in 2017, primarily due to investments in the Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP). This surge is driven by the government's policy, such as the 2020 export ban on raw nickel ore, which has led to the establishment of over 60 smelters and positioned Indonesia as a key player in the global EV supply chain.

In 2025, the government has set a nickel ore mining quota of 298.5 million wet metric tons (wmt), an increase from 271.89 million wmt in 2024. To further boost national revenues, Indonesia plans to increase mining royalties for nickel, with new rates ranging from 14% to 19%, depending on market prices. This shift aims to balance economic growth with the sustainable management of the country's vast nickel resources while meeting the growing demand for nickel, especially for electric vehicle batteries.

Box 1 – Nickel Royalty Hike in 2025: Impact on Projects and Investment Confidence

One of the biggest policy changes in 2025 was Indonesia's overhaul of mining royalties, aimed at capturing more value from its critical minerals boom. Effective April 2025, the government raised nickel ore royalties from a flat 10% to a sliding scale of 14% up to 19% (of sales value), depending on the nickel benchmark price. Royalties on processed nickel products also jumped: ferronickel and nickel pig iron now incur 5–7% (up from 2–5%), and nickel matte (an intermediate for batteries) 4.5–6.5% (up from 2–3%). The new structure is value-based, aligning royalties with international prices and nickel content, rather than a fixed rate.

For the government, the royalty hike serves multiple goals. It boosts state revenues to fund priorities (infrastructure, food security, defense), and it doubles down on the "resource to industry" vision of President Prabowo Subianto's administration. By rewarding companies that invest in smelters (through lower effective royalty on processed nickel) and penalizing export of raw high-grade ore (which may now attract ~19% royalty), Indonesia is signaling that foreign miners are welcome – but only if they add value locally. Indeed, officials have explicitly tied fiscal policy to industrial policy, stressing that resource extraction must deliver domestic manufacturing gains.

The new royalties have elicited mixed reactions from investors and miners.

By design, the framework favors downstream processing: higher rates apply to unprocessed ore, while refined products enjoy comparatively lower rates. This reinforces Indonesia's push for in-country smelting and battery production, disincentivizing raw ore trade. Investors willing to partner with local entities and move up the value chain can still thrive under the new regime. In effect, the royalty hike may weed out purely extractive ventures while rewarding integrated projects – consistent with Indonesia's broader strategy to be the battery supplier for the EV era, not just a raw material exporter.

Battery Supply Chain

With such fast nickel deposits, Indonesia has been leveraging it to draw in top battery manufacturers. In July 2024, Hyundai and LG Energy Solution inaugurated Southeast Asia's first EV battery cell plant – a $1.1 billion joint venture in Karawang, West Java with an output of 10 GWh per year (enough for ~150,000 EVs). This plant is integrated with Hyundai's car factory and will supply locally made batteries for the Hyundai Ioniq 5 and Kona EV, and Kia models. The partners are already planning a second phase to add 20 GWh more capacity with an extra $2 billion investment. President Joko Widodo lauded this as a milestone that "cements Indonesia's key position in the EV global supply chain", finally adding value to the nation's mineral wealth.

Another battery giant, CATL (China), has a consortium with Indonesian state companies to invest an estimated $6 billion in an end-to-end nickel processing and battery project, and Taiwanese electronics firm Foxconn has teamed up with local conglomerate Indika to explore EV battery and bus manufacturing. By mid-2025, Indonesia has nine facilities processing nickel ore into battery-grade nickel and cobalt sulfate (materials for cathodes); four are operational, three under construction, and two in feasibility stages. These include High Pressure Acid Leach (HPAL) plants in Morowali (Central Sulawesi) and Obi Island (North Maluku) supplying nickel intermediates for batteries. The next planned steps are domestic production of precursors, cathodes, and ultimately complete battery packs to feed the growing EV assembly industry.

Box 2 - Global Battery Trends: A Risky Crossroad

Indonesia's EV supply chain is heavily invested in nickel-rich battery chemistries, but global trends are shifting. Lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries, which do not require nickel or cobalt, are rapidly gaining popularity—particularly in China and India. LFP is cheaper, more thermally stable, and increasingly used even in high-volume export models.

This shift poses a long-term risk to Indonesia's upstream-centric approach. While the country continues to attract investments in HPAL and nickel refining, the global move toward LFP and even sodium-ion technologies may eventually reduce demand for nickel in entry-level EV segments.

EV Manufacturing

Five automakers now operate EV plants in Indonesia, up from zero before 2022. South Korea's Hyundai Motor Group was an early mover – it opened a vast new manufacturing plant in Cikarang (West Java) in 2022 with capacity for 250,000 vehicles/year, including up to 70,000 EVs annually. Chinese automakers followed: Wuling Motors (SGMW) launched EV assembly in 2022 at its West Java factory (capacity 120,000 units/year for both EV and conventional cars), and newer Chinese entrants like Chery and DFSK began assembling EV models through local partners by 2023.

In 2024, two more foreign EV makers committed to Indonesia: GAC Aion (China) is building a plant in West Java to produce 30,000 EVs/year by 2025, and Vietnam's VinFast started constructing a plant (50,000 units/year capacity) in Java with a $200 million investment. Meanwhile, BYD (China) – the world's second-largest EV producer – has pledged a $1 billion investment for a new factory in Indonesia by 2026 (targeting 150,000 units/year), after intensive courting by Jakarta. Japan's automakers, long dominant in Indonesia's auto market, are pivoting too: Toyota announced an Rp 27.1 trillion (~$1.8 billion) plan to produce EVs in Indonesia by 2027 (starting with hybrid models and scaling to battery EVs), and Mitsubishi and Honda have launched hybrid models with local assembly as a stepping stone to full EVs.

Key EV Manufacturing Projects in Indonesia

These investments underscore Indonesia's strategy: build an end-to-end EV industry domestically – from mineral extraction and processing in the islands, to battery cell manufacturing, to vehicle assembly in Java – positioning the country as a one-stop regional EV production base. The influx of foreign automakers and battery firms also brings technology transfer and jobs. North Maluku province alone attracted $9.8 billion of investment in 2022 tied largely to nickel processing and battery materials, driving its GDP up 23% in Q2 2023. Meanwhile, West Java, already Indonesia's automotive manufacturing heartland, is becoming the assembly hub for EVs, with established infrastructure, skilled labor, and new dedicated industrial zones for EV and battery projects.

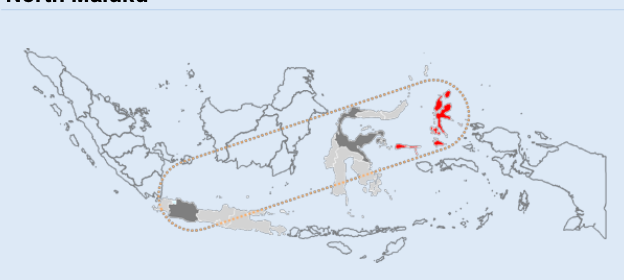

Box 3 - Provincial Hotspots: North Maluku, Central Sulawesi, and West Java as EV Ecosystem Pillars

North Maluku

Particularly Halmahera Island is the ground zero for the upstream EV battery boom (which has transformed the local economy: North Maluku's GDP growth topped 20% in recent quarters, and thousands of jobs have shifted from fishing or farming to mining and processing). The island's laterite nickel deposits have given rise to giant nickel industrial parks that supply critical materials for lithium-ion batteries. The Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) in Central Halmahera is a centerpiece: a sprawling complex of mines, smelters, and chemical plants, co-owned by Chinese stainless steel giant Tsingshan and French miner Eramet. Since starting operation in late 2019, Weda Bay has ramped up so fast that it now accounts for 17% of global nickel production – a staggering figure illustrating Indonesia's dominance in nickel. Within a decade, Indonesia grew to produce almost half of the world's nickel output, much of it concentrated in Halmahera and neighboring Sulawesi.

The government's nickel ore export ban (enforced since 2020) forced companies to build processing onshore, leading to several HPAL refineries in North Maluku that extract nickel and cobalt sulfate for batteries. For example, on Obi Island (South Halmahera), PT Halmahera Persada Lygend's HPAL plant began producing Mixed Hydroxide Precipitate (MHP) in 2021 – one of the first of its kind in Indonesia. These facilities, along with planned precursor and recycling plants, form the upstream anchor of Indonesia's EV supply chain. Looking ahead, North Maluku – with ongoing Chinese, Korean, and Japanese investments – is poised to remain the mineral and chemical production hub powering Indonesia's battery dreams. The province's strategic role is even recognized in policy; for instance, the government is developing a "Battery Industry Zone" there, complete with a seaport and power plants, to streamline logistics for exporting nickel-based materials (and potentially batteries) to Java and beyond.

West Java

In contrast, West Java sits at the other end of the EV supply chain, emerging as Indonesia's manufacturing and logistics hub for EV assembly and distribution. West Java has long been the nation's automotive heartland, home to clusters of factories for Toyota, Daihatsu, Mitsubishi, and others. Now, it's fast adapting to electric mobility. The corridor east of Jakarta (Bekasi-Karawang-Purwakarta) hosts several new EV facilities. The Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Indonesia plant in Cikarang (Textile City/Deltamas area) is the flagship EV car factory, producing the Ioniq 5 and (from late 2024) the Kona EV primarily for the domestic market.

Nearby, Wuling's plant in Bekasi churns out the Air EV mini-cars, some of which have even been exported within Southeast Asia. These locations are advantageous as they sit on major toll roads connecting to Jakarta's consumer market and Patimban deep-sea port in Subang (a new port geared for automotive exports). Indeed, Indonesia's first batch of EV exports (hundreds of Wuling Air EVs to Thailand and beyond) shipped out from West Java in 2023, utilizing this growing infrastructure. West Java is also where the supply chain comes together: the HLI Green Power battery cell plant (Hyundai-LG JV) in Karawang supplies batteries just-in-time to Hyundai's car line a few kilometers away, exemplifying the integration of upstream and downstream activities within the province. The province has attracted not only big car OEMs but also numerous supporting investments: electric bus assemblers (BYD and local partners are setting up an e-bus facility in Bandung), battery pack and module makers (several local firms in Bekasi), and charging infrastructure startups. The local government, keen on positioning West Java as an "EV Province," offers incentives like expedited permits and has designated parts of Bekasi and Karawang as special EV industrial zones.

Central Sulawesi

This Province rivals Halmahera as a nickel-processing hub with the Indonesian Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) hosting multiple smelters and two HPAL plants under construction; Jakarta (a special province) is a pilot city for EV public transport, with plans to convert TransJakarta buses to electric and add thousands of charging spots in the capital. Bali has been earmarked as a showcase "EV Island" where only electric buses will serve tourists by 2030. And the newly developing North Kalimantan green industrial zone (utilizing abundant hydropower) has invited EV and battery manufacturers to set up with 100% renewable energy - an attractive proposition for companies with sustainability mandates. But for now, North Maluku and West Java remain the twin pillars: one providing the raw and semi-processed materials, the other assembling the finished vehicles and coordinating distribution. The synergy between a mineral-rich east and an industrialized west is at the core of Indonesia's EV strategy to become a self-reliant regional leader.

2. Domestic EV Adoption and Projections to 2030

Indonesia's EV market posted record growth in 2024. Battery electric vehicle (BEV) car sales surged to 43,188 units, a 151% year-on-year increase. This puts Indonesia's EV penetration at around 5% of national car sales. In the two-wheeler segment, electric motorcycles crossed the 100,000-unit mark for the first time, fueled by targeted government subsidies.

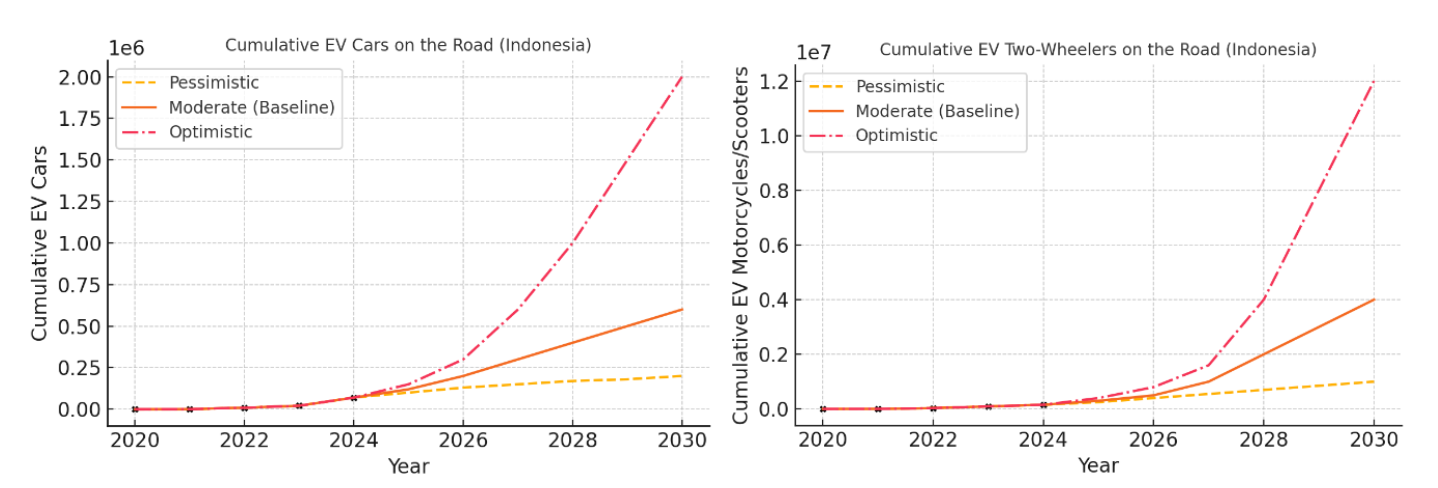

To understand Indonesia's EV trajectory, we look at future adoption scenarios and the supporting infrastructure required. The government's official target, 15 million EVs on the road by 2030, comprises 2 million electric cars and 13 million electric motorbikes. Achieving these numbers within 5–6 years is extremely ambitious, considering that as of late 2024, only around 50 thousand EV cars and perhaps a few hundred thousand e-motorbikes (mostly low-speed scooters) are in use. It implies a steep S-curve of adoption ahead. Even a more conservative scenario from independent analysts (for example, the International Energy Agency) still envisions several hundred thousand EVs in Indonesia by 2030 if current policies persist.

EV Adoption Projections (2025–2030)

We project EV adoption from 2025 through 2030 under three scenarios: Pessimistic, Moderate (Baseline), and Optimistic - to capture uncertainty in policy, technology, and consumer behavior. All scenarios assume charging and battery-swapping infrastructure expands sufficiently and does not constrain growth (i.e. ample charging stations or swap stations in all major regions). We focus on battery-electric cars (four-wheelers) and motorcycles/scooters (two-wheelers), excluding hybrids.

For all scenarios, total vehicle population growth is assumed to continue. Indonesia had ~11 million passenger cars in 2022 and ~133 million motorcycles in 2023; by 2030 these may reach ~15 million and ~180 million respectively (assuming moderate economic growth). We use these as denominators to estimate EV market share. Below we present annual EV sales, cumulative fleet, and market shares for each scenario, along with regional breakdowns for key provinces.

Moderate (Baseline) Scenario

The Moderate (Baseline) scenario shows EV adoption growing steadily but not hitting all government targets. Annual EV car sales rise from ~60–100k in 2025 (about 5–8% of new cars) to ~120–150k by 2028 (15–20% of new sales), and then ~180k (≈30% of new sales) by 2030. Cumulatively, this yields around 600,000 EV cars on the road by 2030 (roughly meeting the Ministry of Industry's goal of 20% of new car production being EVs by 2030).

Electric two-wheeler sales in this scenario might reach 200–300k per year by the late 2020s – a huge increase from ~60k in 2024, but constrained by phased-out subsidies and slower consumer uptake in rural areas. The e-two-wheeler fleet grows to about 4 million by 2030. This is a significant jump (Indonesia would likely be among the top EV two-wheeler markets globally), yet it is only ~2% of all motorcycles.

Key Assumptions:

- Policies and adoption improve at a steady pace without drastic measures

- Aligns with official industry roadmaps

- EV purchase incentives gradually taper as EVs become more affordable

- Growth is significant but falls short of the lofty 2030 targets

- Roughly on track for ~30% of new vehicle sales being electric by 2030

| Projected EV Adoption by 2030 (Optimistic vs. Baseline vs. Pessimistic) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | EV Cars (2030) | EV Two-Wheelers (2030) | EV % of Car Fleet (2030) | EV % of 2W Fleet (2030) |

| Optimistic | ~2,000,000 | ~12,000,000 | ~13% | ~7% |

| Moderate | ~600,000 | ~4,000,000 | ~4% | ~2% |

| Pessimistic | ~200,000 | ~1,000,000 | ~1% | ~0.5% |

| (Percentages are approximate, assuming ~15 million cars and ~180 million two-wheelers on road by 2030.) | ||||

The share of EVs in annual new sales is expected to be much higher than the fleet percentages above by 2030, especially in the optimistic case. For example, in the moderate scenario, EVs might make up ~30% of new car sales and ~20% of new motorbike sales in 2030, even though they comprise only a single-digit percent of the total vehicles in use. This indicates a tipping point around 2030 where EV adoption could rapidly accelerate beyond our forecast horizon, as upfront costs fall and secondhand EV markets develop.

The projections above focus solely on privately owned vehicles and do not include the additional EVs that public transport and mobility operators plan to deploy. Major fleet operators—like TransJakarta, Blue Bird, Xanh SM, Gojek and Grab—have all announced ambitious electrification targets that will further boost overall EV uptake

Box 4 – Some Notable EV Adoption Plans by Public Transport Fleet Operators

| Operator | Current EV Fleet (2025) | Target / Plan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TransJakarta | 200 electric buses | 50% of fleet by 2025; 100% by 2030 | Aims to electrify 10,047 buses by 2030. |

| Blue Bird | ~400 electric taxis | 1,000 EVs by end-2025; 10% of fleet by 2030 | Plans to expand EV fleet to 1,000 units by 2025. |

| Xanh SM | ~100 EV taxis (launched Dec 2024) | 10,000 EVs by end-2025 | Entered Indonesian market in Dec 2024; plans for rapid expansion. |

| Gojek (Electrum JV) | Pilot phase; limited deployment | Transition to 100% EVs by 2030 | Partnership with TBS Energi; early-stage deployment. |

| Grab | More than 10,000 electric two-wheelers | Add 1,000 BYD EVs by end-2024; expand EV fleet regionally | Largest EV fleet operator in Indonesia; plans to add 1,000 BYD EVs. |

3. Charging Infrastructure Progress

Public charging infrastructure remains limited. As of 2024, there were about 1,566 public charging stations nationwide—well below the levels required for mass adoption. The state-owned utility PLN aims to scale this network to over 63,000 stations by 2030. However, most current stations are concentrated in Java and Sumatra, with minimal coverage elsewhere.

Projected Growth of Public Charging Infrastructure (2024-2030)

Private sector plans—such as VinFast's commitment to roll out over 100,000 charging points—remain mostly at the planning or pilot stage, and deployment timelines are still uncertain.

Charging Infrastructure Gap

A major challenge is building out charging infrastructure at pace with the vehicle growth. Based on the government's 2030 EV target, the Energy Ministry estimates about 32,000 public charging stations (known as SPKLU) will be needed by 2030 to meet demand. State-owned utility PLN's own roadmap (aligned with a more moderate EV uptake scenario) projected the need for 24,720 charging stations by 2030. These figures are orders of magnitude above the current network. As of April 2024, Indonesia had just 1,566 charging stations installed nationwide. Even by including slower AC chargers and thousands of private home chargers, the gap is enormous. To bridge it, the government aims to add up to 48,118 charging points by 2030 through public-private partnerships and PLN investments. This presumably includes not only standard public chargers but also fast-charging hubs along highways and destinations.

Box 5 - Spatial distribution

Infrastructure will need to be concentrated in urban centers and major transit routes first. Jakarta (metro population ~30 million) is expected to account for a large share of early EV adoption, so the city is incentivizing installations in malls, parking lots, and even street lamp-post chargers (an innovative PLN project attaches chargers to existing utility poles for space efficiency). Other big cities like Surabaya, Bandung, and Medan have launched "EV zones" with a few dozen chargers each. For the burgeoning highway network, PLN has built fast-chargers on the Trans-Java toll road at intervals of ~100 km, as a pilot to enable inter-city EV travel. However, inter-province connectivity remains poor – for instance, driving an EV from Jakarta to Bali (1,200 km) is still a challenge due to sparse charging in the middle stretches. By 2030, the plan is to have all Trans-Java and parts of Trans-Sumatra highways equipped with ultra-fast chargers at rest areas, akin to the Tesla Supercharger network model.

For electric two-wheelers, the strategy leans towards battery swapping stations rather than traditional plug-in chargers, to minimize wait times for riders. The government has encouraged petroleum companies and startups to set up swap station networks. By some plans, around 67,000 battery swap kiosks may be required to support the millions of e-bikes targeted (this was mentioned in a draft ministry plan). Currently, there are fewer than 1,000 swap stations (mainly pilot projects in Jakarta and Bali).

Economic modeling of demand

An analysis by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) modeled Indonesia's charging needs under different EV uptake scenarios. In a scenario meeting the government's 2 million EV car target by 2030, the ratio of EVs per charger might need to be around 60:1 (similar to Europe's current ratio) to adequately serve drivers. This implies tens of thousands of public chargers as noted. The investment required for such infrastructure is substantial – rough estimates are in the range of $2–3 billion (for hardware, installation, grid upgrades, and land). The government has called on private investors to step in, offering incentives such as 0% import duty on charging equipment and allowing charging service providers to trade electricity at special tariffs. Several state-owned firms and startups have responded: for example, Pertamina (the national oil company) is installing EV chargers at its gas stations, and a startup called Electrum (a JV of Gojek and TBS Energi) is rolling out battery swap stations for electric motorbike fleets in Jakarta.

By 2030, under an optimistic scenario, one could expect: around 1.8–2 million EV cars on the road, mostly in Java and Bali, and perhaps 8–10 million electric two-wheelers nationwide (assuming the government's 15 million total EV goal is partially met). Correspondingly, there might be on the order of 20,000–30,000 public chargers installed (scaling up from current commitments) and tens of thousands of battery swap points for bikes. These numbers, while huge jumps from today, would still mean an EV-to-charger ratio higher than developed countries – which is plausible given many Indonesian EV owners may charge at home or work. The key is that chargers need to be strategically located to alleviate range anxiety and enable long-distance travel, otherwise EV uptake could stall out below targets.

Electric Grid Capacity

Crucially, the electric grid capacity must keep up as well. PLN has projected that powering 15 million EVs would require several additional gigawatts of generation. Indonesia currently has surplus capacity in Java at off-peak times (due to many new coal plants coming online), which could actually accommodate night-time EV charging load. The government is also pushing smart charging and solar integration (e.g. encouraging EV charging stations to have rooftop solar and battery storage). By electrifying transport, Indonesia aims not only to cut CO₂ and oil imports, but also to improve its energy security. An official calculation suggests that reaching the 15 million EV target would save ~29.7 million barrels of oil equivalent in fuel and cut 7.2 million tons of CO₂ emissions in 2030 - a significant contribution to climate goals if achieved.

4. Policy Support and Industry Incentives

Indonesia's government has enacted sweeping policies to cultivate a full EV supply chain from minerals to markets. A 2019 regulation laid the groundwork for EV industry development, and by 2023 the government rolled out generous incentives. Notably, value-added tax (VAT) on EV purchases was cut from 11% to 1% for locally made EVs with at least 40% local content. For 2024, authorities removed the luxury sales tax on EVs and waived import duties through 2025, on the condition that foreign automakers start producing locally by 2026 to match any imports. These incentives aim to make EVs more affordable and attract foreign manufacturers, while local content rules ensure investment in domestic supply chains. The government has also allocated hefty subsidies for two-wheelers. In 2024, a purchase subsidy of Rp 7 million (~USD 435) per electric motorcycle was rolled out, quickly driving up sales. The government also supports vehicle conversions and mandates local content requirements to deepen industrial capacity.

Box 6 - Policy Failure?

Indonesia's electric motorcycle conversion subsidy program, despite offering Rp 10 million per unit, has largely failed to meet its objectives, with only 1,111 units converted in 2024 - far below the original 50,000 target. Structural barriers such as high remaining costs for consumers, limited certified workshops, low public awareness, and distrust in post-conversion quality have led to poor uptake and left over Rp 349 billion in unabsorbed funds. The program's underperformance highlights critical gaps in policy design, execution, and outreach, undermining its role in Indonesia's broader EV transition.

At the same time, policy implementation has faced fragmentation at the sub-national level, with local regulations and readiness varying across provinces. Accelerating the rollout of EV infrastructure, simplifying investment licensing, and improving clarity around local incentives will be crucial going forward.

| Policy Area | Indonesia | Thailand | Vietnam | India |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase Subsidies | Yes – bikes & cars | Yes – cars & bikes | Yes – mostly bikes | Yes – FAME-II scheme |

| Import/Luxury Tax Relief | Full exemption | Reduced excise taxes | Partial incentives | GST cut for EVs |

| Local Content Requirements | 40-60% TKDN rule | Light mandates (25%) | None | 50%+ to access incentives |

| Battery Manufacturing Incentives | Tax holidays, JV support | BOI support & subsidies | Early-stage support | PLI scheme + infra funding |

| Charging Infrastructure Rollout | 1,566 chargers (slow) | 3,500+ chargers + roadmap | <1,000 public chargers | >12,000 stations & scaling |

| Electric 2W Market Maturity | Growing (~100k units) | Mature (~1.5M units) | Strong (~400k units) | Largest (>2.7M units/year) |

| Battery Cell Production Capacity | 10 GWh in 2024 | 16-30 GWh by 2030 | Early stage | >150 GWh by 2030 (targeted) |

| EV Mandates for Govt Fleets | Presidential instruction | Gov't fleet roadmap | Not yet | Central + state-level orders |

| Conversion Programs (ICE → EV) | Motorcycle conversion | Pilots only | None | Commercial retrofits allowed |

| Public Awareness Campaigns | Limited | Active outreach | Limited | Nationwide campaigns |

Indonesia also provides import tariff exemptions for both CKD and CBU EVs, helping reduce upfront costs for imported units although these apply only until end-2025 and require a commitment to local manufacturing. Additionally, all EVs are exempt from annual vehicle taxes (PKB), which can range from 1.2% to 10% of the vehicle's value, and from title transfer fees (BBNKB), which normally reach up to 12–20%. These measures aim to reduce the total cost of EV ownership and encourage adoption, particularly in the used vehicle market, though awareness and implementation consistency across regions remain areas for improvement.

5. Competing for EV Supremacy: Indonesia vs. Thailand, Vietnam, and India

Indonesia is not alone in chasing EV investments as it faces stiff competition from regional peers who also aspire to be EV manufacturing hubs. Here we compare Indonesia's position with Thailand, Vietnam, and India on key metrics: incentives, infrastructure, regulatory climate, and realized vs. announced foreign direct investment (FDI). regulatory climate, and realized vs. announced foreign direct investment (FDI).

EV Market Share Comparison in Southeast Asia (2024)

Thailand

"Southeast Asia's EV Leader"

- EV Sales: In 2024, Thailand registered 70,137 EVs, marking a 10.4% decrease compared to 2023.

- Market Share: EVs accounted for 12.25% of total new vehicle sales in Thailand in 2024.

- Government Incentives: The Thai government offers subsidies up to 150,000 baht (~$4,400) per EV and has implemented policies to reduce import duties and taxes for EV manufacturers.

- Manufacturing Investments: Chinese automakers, including BYD, Great Wall Motors, and SAIC, have established or are constructing EV factories in Thailand, leveraging the country's robust automotive infrastructure.

- Production Goals: Thailand aims for 30% of its annual vehicle production to be electric by 2030, equating to approximately 750,000 units.

Vietnam

"Homegrown EV Development"

- EV Sales: In 2024, Vietnam's EV sales reached nearly 90,000 units, a 2.5-fold increase from the previous year.

- Market Share: EVs constituted approximately 16% of new vehicle sales in Vietnam in 2024.

- VinFast's Role: VinFast, Vietnam's leading EV manufacturer, delivered over 87,000 EVs domestically in 2024 and is expanding its global presence with new factories in the U.S. and India.

- Government Support: Vietnam offers a zero-percent registration fee for EVs through 2027 and exempts EVs from consumption tax until the same year, promoting EV adoption.

- Foreign Investment: Vietnam is attracting foreign investment in EV components and battery manufacturing (e.g.LG Chem).

India

"Rapidly Growing EV Market"

- EV Sales: India's EV sales reached approximately 1.95 million units in 2024, accounting for 7.4% of total vehicle sales.

- Market Composition: Electric two-wheelers and three-wheelers dominated the market, comprising 94% of total EV sales. Electric cars and SUVs accounted for about 5% (nearly 100,000 units sold).

- Government Initiatives: India's government launched the PM Electric Drive Revolution in Innovative Vehicle Enhancement (PM E-DRIVE) scheme to promote EV adoption and expanded public charging infrastructure with 25,202 new stations nationwide in 2024.

- Market Leaders: Tata Motors remained the top EV seller in India, with 61,496 units sold in 2024.

- Foreign Investment: VinFast announced a $2 billion investment to build an EV manufacturing facility in, India, aiming to produce up to 150,000 vehicles annually.

Indonesia has seen major projects break ground (Hyundai-LG, Hyundai auto plant, Wuling, etc.). Thailand has a higher proportion of its EV announcements translated into operating factories to date. Vietnam's FDI is largely VinFast's own spending, while India's is mostly domestic with some big-ticket foreign projects just starting. Indonesia's selling point is the complete supply chain vision – a car made in Indonesia could also have an Indonesian-made battery and Indonesian-mined nickel, all benefiting from tax breaks and a growing domestic market. If it can execute this vision, Indonesia could indeed become the regional leader, but it must outpace a very capable Thailand and respond deftly to moves by Vietnam and India.

6. Gaps and Challenges: Bridging the Way to Regional Leadership

In overall, while Indonesia's electric vehicle (EV) ecosystem is progressing rapidly, several policy and investment gaps could hinder its ambitions to be the regional leader. Addressing these gaps is crucial for ensuring the nation to achieve its targets.

1. Charging and Grid Infrastructure

The charging network in Indonesia is significantly lagging behind the nation's ambitious EV adoption goals. Insufficient infrastructure, particularly outside Java's major cities, poses a major risk to mass adoption. Regulatory hurdles, such as licensing for private operators and unclear electricity tariff structures, exacerbate the situation. Fast charger installations are slow, with high permitting costs and necessary grid upgrades hindering progress. A clear national EV charging roadmap, supported by funds (possibly from nickel royalties or fuel subsidy savings), is essential to accelerate deployment and reduce reliance on state-owned PLN.

2. High EV Costs and Limited Model Availability

Despite tax cuts, EVs remain far more expensive than conventional vehicles in Indonesia, with prices for even small EVs exceeding USD 20,000. The government's focus on subsidizing electric motorcycles has left car adoption underfunded. This price gap, coupled with a limited range of EV models, especially in the affordable segment, continues to deter widespread adoption. Direct consumer incentives, along with low-interest financing options and the acceleration of homologation for imported models, could help expand the market and encourage more choices for consumers.

3. Supply Chain Integration and Quality

Indonesia's push for EV adoption has been largely government-driven, with insufficient attention to building a broader supply chain ecosystem. The country lacks a robust base of local component suppliers for EV parts and needs a trained workforce skilled in battery technology, power electronics, and software. Unlike Thailand, which has a well-established auto parts industry, Indonesia must cultivate its supplier base and invest in vocational training programs. Failure to address these supply chain and human capital needs will leave Indonesia reliant on foreign expertise.

4. Technology Shifts (Battery Chemistry Risk)

Indonesia's bet on nickel-based batteries could face challenges due to the rapid evolution of battery technology. Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) batteries, which are cheaper and do not require nickel or cobalt, are gaining market traction, particularly in China. If automakers pivot to LFP technology, demand for nickel-based EV batteries could slow. Indonesia must diversify its battery technology strategy by investing in alternative chemistries, including LFP and solid-state batteries, to remain flexible and competitive in the global market. The formation of the Indonesia Battery Corporation (IBC) positions the country to explore these new opportunities, but attention must be paid to emerging global research and trends.

5. Environmental and Social Sustainability

Indonesia's rapid push for EV manufacturing is paradoxically reliant on resource extraction that can harm the environment. Protests against nickel mining and processing, particularly in regions like Halmahera and Sulawesi, highlight the social and environmental risks. Indonesia must align its EV strategy with sustainable practices, including reforestation and green mining standards, to avoid reputational damage. Strengthening Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards will not only mitigate these risks but can also make Indonesian-produced EV batteries more attractive to global eco-conscious markets.

6. Market Coordination and Demand Uncertainty

A significant gap exists between EV production and domestic demand. Indonesia's manufacturing capacity is projected to ramp up significantly by 2027, but without adequate demand, these factories may remain underutilized. Indonesia lacks Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with major EV markets, which could lead to tariff barriers for exports. Neighboring Thailand has secured export agreements through FTAs, allowing its EVs to enter global markets more easily. Indonesia must address this gap by negotiating trade agreements that facilitate EV exports and harmonize regional EV incentives within ASEAN.

-- ¤ --

Key References:

- Argus Media (2024). Indonesia Plans 15 mn Electric Vehicles on Roads by 2030

- ASEAN Briefing (2024). Indonesia Increases Mining Royalties in 2025: What It Means for Investors

- Asian Development Bank (2023). Electric Vehicle Policy Toolkit for Southeast Asia

- ASEAN Secretariat (2023). ASEAN EV Policy Harmonization Study

- Bappenas, Indonesia (2021). National Energy Policy

- Center for Strategic and International Studies (2024). Indonesia's Battery Industrial Strategy

- fDi Intelligence (2024). South-east Asia's EV Investment Race

- GAIKINDO (2024). Automotive Industry Statistics: Electric Vehicle Sales

- International Council on Clean Transportation (2024). Indonesia EV Charging Infrastructure Report

- International Labour Organization (2023). Employment Impacts of the Electric Mobility Transition

- JLL Research (2024). Indonesia's Rise as an EV Hub

- McKinsey & Company (2024). Capturing Growth in Asia's Emerging EV Ecosystem

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, Indonesia (2025). EV Charging Infrastructure Roadmap

- Ministry of Industry, Indonesia (2024). National EV Industrial Blueprint

- Ministry of Transportation, Indonesia (2024). EV Public Transport Integration Plan

- Pirmana, A., et al. (2023). Input–Output Analysis of Indonesia's EV Value Chain

- PwC Indonesia (2024). Electric Vehicle Readiness and Consumer Insights Survey

- Reuters (2023). Indonesia Tax Cut Drives Electric Car Sales

- Reuters (2024). Hyundai Motor, LG Energy Launch First EV Battery Plant in Indonesia

- SCMP (2024). Indonesia's Electric Dream? A Race to EV Supremacy

- UN ESCAP (2024). Asia-Pacific EV Investment Report

- World Bank (2025). Indonesia Economic Prospects: Navigating the EV Transition

- World Economic Forum (2024). Electrifying Public Transport in Southeast Asia

About Indonesian Business Council

The Indonesian Business Council is an association of Indonesia's business and industry leaders, committed to advancing the nation's competitiveness and long-term prosperity through strategic and effective public policy.

Research Team

The IBC Institute

Research. Collaboration. Impact

This report provides a quick analysis intended as an initial alert and insight for readers. It is synthesized from multiple sources and is not a comprehensive assessment. Readers are encouraged to conduct further analysis and verification to gain a deeper understanding. While efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, this report may contain errors, omissions, or imperfections. IBC assumes no liability for any decisions or actions taken based on this report, and readers are advised to exercise their own judgment and due diligence.